This semester I’ve been helping Susan Fernsebner, UMW professor extraordinare, with her section of HIST 297: History Colloquium. This course serves as “an introduction to the methods historians use to analyze the past,” and all three sections, each taught by a different member of the department, are focusing on digital skills not as an add-on, but as a critical, integrated part of the course. Susan wrote a great post this past summer that outlines the structure and purpose of HIST 297, as well as the intentionality with which the department decided to spread what used to be a one-semester methods course into a two-semester sequence. You should go read her entire post on the subject (it’s not long! go read it now!), and I’m hopeful that she will have the time and opportunity to write more about this as the semester starts winding down.

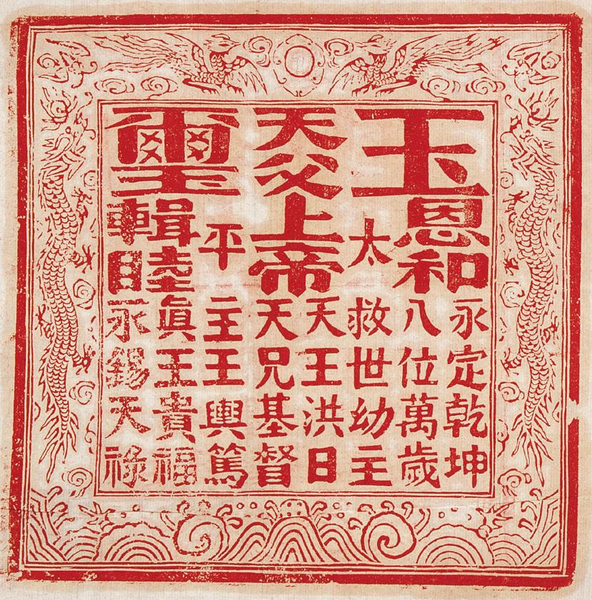

Seal of the Taiping Revolution, via Wikimedia Commons.

The basic goal of HIST 297 is to introduce students to the methods historians use to analyze (and, thereby, to construct, expand, and enrich the world’s knowledge of) the past. Instead of setting up a series of paper-based assignments that will most likely be stored away in a box somewhere after it’s been graded, or perhaps just tossed out altogether, the idea is to have students learn about these methods by using them — in this case, to create a meaningful resource that will contribute to the discourse around the Taiping Rebellion. In order for that to happen, this resource can’t be kept private, or made public but then cleaned out and re-done by students in a later semester. Instead, it needs to be publicly accessible, and also to live on past the end of the semester. (Perhaps UMW students in a future semester will even have an opportunity to expand upon and improve the great work the Fall 2013 students have already done.)

To that end, I’ve worked with Susan and her students to build the digital structure for this project. That includes the website, TaipingCivilWar.org, as well as some of the tools used to construct the resources (including the Knight Lab’s Timeline software, Skype, and Ecamm Call Recorder.) There’s one tool in particular we used that I wanted to outline in some detail; it has a lot of potential, but I don’t think very many people know about it, or have spent much time using it. It’s called the Spreadsheet Mapper, provided by the Google Earth Outreach team.

What’s the project?

Students formed small groups, analyzed primary sources related to the Taiping Rebellion (aka the Taiping Civil War), and compiled selected pieces of information into web-based resources. One of these small groups was tasked with creating an interactive map of important places that would help geographically contextualize the war, including not just battlefields, but also sites of proclamations, inscriptions, and other war-related events.

Tools we picked

We decided to use Google Maps for this piece of the project, as it’s a platform that is free, likely to be around for a while, and doesn’t require much technical knowledge to get started. That said, creating a Google Map can be tedious, and we wanted to make sure students were focusing their time and energy where it belongs, on the primary source analysis. I discovered that the Google Earth team had created a document called Spreadsheet Mapper that would make the map creation process easier.

How it works

To get started, you’ll need to copy the Spreadsheet Mapper document to your Google Drive account. The document comes pre-populated with several sheets (look for the tabs at the bottom of the screen): one that contains some initial setup instructions (called “start here”), one to hold the data about the markers you’ll be creating (called “PlacemarkData”), several that contain the code for some pre-fabbed display templates, and last but not least one that is used to generate the KML code that Google Maps and/or Google Earth use to convert your spreadsheet’s rows into markers on a map. You can safely ignore the template and KML sheets for now; the “start here” and “PlacemarkData” sheets are probably the only ones you’ll be using.

First walk through the tutorial for initial configuration, then switch over to the PlacemarkData sheet. You’ll see the document comes pre-filled with locations in San Francisco, and that each of the various pre-fab display templates is used at least once. You can quickly and easily decide which one(s) you want to use by going back to the “start here” tab, and using the link near the bottom of the sheet to view your data in either Google Earth or Google Maps.

To create new markers on the map, either overwrite the existing marker information, or enter information into a new row of the spreadsheet. You have the choice to use either lat/long coordinates or a street address; street addresses are more familiar, but they make the map slower to load, because the addresses will be converted to coordinates in the background every time a visitor loads the map. Do everyone a favor and use coordinates.

Next, you’ll want to fill out the information that will display in the balloon after a visitor to your map clicks on a marker. Make sure the number of your chosen template is in the “Template #” cell in the row you’re working on, then fill out the information the template calls for.

When you’re ready to make your map available, go to the “start here” page and open the Google Maps link. Find the chain-link sharing icon near the top, and either copy the URL you’re given, use the standard embed code, or use the “Customize and preview embedded map” option. I like to customize the map, which lets you make it larger, change where the map is centered, and set some other defaults. Copy and paste the resulting embed code into your website, and voila! You’re done. Any changes you make to the Spreadsheet Mapper after this point WILL go to the right place; you don’t have to re-embed the map every time you make a change. Here’s a (non-interactive) example of what you might end up with:

What we learned

Using the Spreadsheet Mapper was overall a pretty positive experience, but we did experience some bumps and bruises along the way. Here’s a roundup of the positive and negative issues we noted:

Spreadsheets aren’t just for accountants

One of the students in the class noted that she didn’t realize spreadsheets could be used to do all sorts of cool stuff, not just crunching numbers. I pointed out that there are loads of templates freely available to Google Drive users, not just spreadsheets but documents, presentations, forms, etc. It was pretty cool to see a student realize that there was some creative potential in what might otherwise seem like a really boring, dry, old tool.

Not DIY for students

This is not a tool I would expect students to be able to use with limited guidance — they may not have experience using spreadsheets for projects like this, and even if they are, there’s a lot going on in this this particular spreadsheet, which makes it unintuitive. There are lots of instructions to read and make sense of, and lots of fine details to keep in mind. For example, the way the template selection works is a little bit confusing; version 2 of the Spreadsheet Mapper includes a template overview at the top of the sheet that let you know which templates use which fields. Theoretically, you’d use this overview to remind yourself which template you wanted to use for a given row, but in practice I think this was distracting and a little confusing for the students, and for me as well. If you’re interested in using the Spreadsheet Mapper, I would recommend alloting some face-to-face time to explain how it works, have each student fill out a single row or two, and then give them a chance to ask any followup questions right away. This took about 30 minutes of class time, but once students understood all the moving parts, they were off and running.

Formatting text by hand

Students reporting they were very comfortable with entering text into the spreadsheet, because it was easy and familiar. One potential downside, though, was the lack of visual formatting options. If students wanted to make a string of text into a clickable link, for example, they had to hand-craft the HTML code to make that happen.

Coordinates are easy to find

For most well-known locations, doing a Google search for “[location] coordinates” will usually give you the latitude and longitude for a location. That works for specific locations, and also if you just need a marker to represent a city or town more generally.

Wikipedia is also a source for coordinates; if a location has an Wikipedia article, check the info summary box in the top right corner of the article. If all you have is a street address not directly connected with a famous building, you can also use LatLong.net to convert that address into the correct coordinates. [UPDATE: Trip Kirkpatrick from Yale suggested two additional geocoordinate lookup tools in the comments. Go see them!] Just remember: when you put these coordinates into the spreadsheet, northern latitudes and eastern longitudes should be entered as positive numbers, while southern latitudes and western longitudes should be entered as negative numbers.

Changing templates means redoing work

Originally, the students in this class had picked one template, because it was laid out well and could display a photo. Once they started creating their entries, though, they realized they weren’t going to have any photos or images to display along with the text. So, they decided to switch gears and use a different template. Because different templates use the same columns for different information, the students had to go back and reorder the information they’d already collected. It wasn’t a huge loss of time, given the small number of locations they were working with, but if you’re planning on using this with a lot of entries I’d recommend starting with 5-10 first, then checking to make sure the template you’ve chosen is working well before proceeding.

Publishing delays are annoying

The Spreadsheet Mapper is a great tool, but it’s not particularly fast. Version 2 would automatically republish the map after you made changes, but there was a delay between making the changes and when the spreadsheet was auto-published, as well as a delay between the auto-publishing and when the new information would actually appear on the map view. This was a little worrisome for students when they first started out and thought they were doing something wrong; once they realized there was just a delay, they were able to adjust their workflows accordingly. Version 3 of the Spreadsheet Mapper does away with auto-publishing; you have to manually republish after you’re done making changes. That does away with the first delay, but the second delay still happens. It’s not a huge deal, but it can be pretty annoying when you have to wait several minutes just to confirm that the small change you made actually looks as you expect.

What we left out

There were a few things we could have done with Spreadsheet Mapper that we decided not to pursue, partially because the Spreadsheet Mapper tool was new to all of us, and partially because we didn’t want to get too bogged down in the technical details.

Access

Since the Spreadsheet Mapper is just a template you copy into your Google Drive account, we had the same privacy / access options we would for any other Google Drive document. We could have collected students’ Gmail accounts and restricted editing access only to those students, but given that the spreadsheet is unlisted (and can’t be found via search), we figured that password-protecting the page where students can access the link was good enough. Sure enough, we haven’t had any problems. Just in case, Susan has been periodically downloading versions of the spreadsheet to her local computer in case we needed to restore something, but that is as much to protect against accidental deletion as it is to fight spam / miscreants.

Versioning

When we got started with this project, the current Spreadsheet Mapper was version 2, but about halfway through the Google Earth team released version 3. While version 3 is (in my opinion) better and easier to use, there were a couple of differences that might be confusing, and I didn’t want to disrupt the work the students were already doing. For example, in version 2, any changes you make to the spreadsheet would be automatically pushed to the embedded version of the map. In version 3, however, you have to manually tell the spreadsheet to republish itself in order for any of your changes to show up. We’ll have a little bit of clean-up to do on the site once the semester is over and everyone’s done with their projects, and I expect that moving the students’ work into the new version will be a part of that process.

Templates

When a visitor clicks on a Google Maps marker, they see a balloon that displays more information about the marker they clicked. When you’re creating a standard Google Map, you don’t have a lot of control over what the balloon looks like — you can add a title and enter either plain text or HTML for the body of the balloon, but that’s about it. The templates that come with Spreadsheet Mapper allow you virtually unlimited control of the balloon: what size are the fonts, what color is the background, where images are displayed, if there is a consistent header and footer, and practically anything else you can imagine. To keep things simple, we had students choose from the six pre-set templates that came out of the box. I imagine that, once we move the students’ work to version 3, we will also spend a little bit of time customizing the balloon display. This would be a great way, for example, to take the students’ citations that currently live alongside the rest of the text, and make them look more like traditional footnotes.

Alternatives

At the time we started this project, I wasn’t aware of a couple of other tools we might have used: namely, Neatline, as well as the other Google Earth tools available online. The Spreadsheet Mapper worked well, and I’m glad we had the hands-on experience of trying it, but if I was supporting a project like this again I’d spend a little time deciding whether another tool might provide a better experience (even if it meant a little bit steeper learning curve).

Final thoughts

This project is a perfect example of why I love working in the liberal arts. I’m always excited and uplifted to watch students learn the critical thinking skills that will serve them well in so many contexts moving forward. As an educational technologist, it’s especially powerful to see students internalize the idea that technology is just another tool they can use to make things happen.

A student in @sfern’s class made my day by saying: “[The technology] isn’t the hard part of this project, the [academic work] is.” <3

— Ryan Brazell (@ryanbrazell) October 16, 2013

All of the resources created by the students are now and will remain available to the general public via TaipingCivilWar.org, the project website. We still have some work to do to clean up what’s there and to include additional resources created by the students, but you can already see the time and effort students put in to make this happen. Word has it that a major peer-reviewed journal in the field has even expressed interest in linking to the project website once it’s ready for prime-time — how cool is that?

I’d love to hear from those of you who have done similar projects, or worked with similar tools. Leave your comments, questions, and/or snide remarks in the comments!